Latest word works, this time for Design Observer, sees my analysis of the state of design and business education. In the past few years, there have been interesting attempts from within both business and design schools to elevate the potential of design and creative thinking as drivers of differentiated value. Yet there are still relatively few graduates from these programs, and their impact and efficacy remain inconclusive. For this piece, I spoke with a number of leaders from within the world’s leading design and business schools about the system and their attempts to produce what writer Daniel Pink describes as the “creators and empathizers, pattern recognizers, and meaning makers” of our future. My conclusion? There’s a big disconnect that these programs don’t come close to fixing.

Thought You Should See This

I recently launched a new site, thoughtyoushouldseethis.com. It’s basically what I thought this blog might be — an online notebook of things I see, read, find interesting or think would in some way be worth noting. In the meantime, I’ve been wondering why I haven’t used this blog for that purpose. And in the end, I think the answer is pretty simple: the “personal brand” trend makes me want to poke my own eyes out. I get it. But it’s not for me. And nabbing Thought You Should See This has freed me up to write about a whole ton of things that didn’t sit right under a headline of my name. Overthinking much? Oh yes. In the meantime, I’ll use this blog as a repository for my own word works, and for random thoughts and musings that I can’t imagine any publication would care for.

Thoughts on Amina, the Straight Man in Scotland

In 2009, I wrote a piece for BusinessWeek‘s innovation blog that told the tale of a guy based in Chicago who tapped his social network for money to help a friend in trouble. He raised $12,000 overnight, and I wrote a story about how amazing it was that such largesse could be harnessed in such a short period of time and how lovely that such generosity and humanity lurked amid the bits and bytes.

Most people agreed. Then a guy called Mark popped up in the comments section. Mark thought the whole thing was a crock, and that I had done BusinessWeek readers an enormous disservice by not traveling to Chicago to verify that the woman existed and was indeed in need.

I asked a senior editor at the magazine what he thought. I mean, our online department had the budget of a gnat. There was no way I’d have been able to travel from New York to Chicago to verify the story. I knew the guy raising the money pretty well and had quoted him in stories before. I trusted him. And anyway, I wasn’t endorsing the fundraising; I was merely reporting on a new phenomenon enabled by the connective tentacles of the Internet and technology. My excuses stuttered on, and the editor fixed me with a look. “Two words,” he said, tartly. “Bernie Madoff.” And with that, he plunged a dagger into my heart and I relearned the unimaginably important lesson at the heart of all journalism: question everything, and then question it again.

It’s a lesson that came to mind with the revelation that Amina, the Gay Girl in Damascus wasn’t anything of the sort (in fact, she was the invention of an American Man in Scotland.) Amina came to the attention of the world’s media after “she” wrote a blog post back in April. In My Father the Hero, she outlined the story of how her father had shamed some thugs who came to their house in the middle of the night to arrest her. The story was raw, powerful and emotional. I cried when I read it, and promptly sent on the link via Twitter, with, I might add, a disclaimer: “No idea if it’s true.”

And, indeed, it turns out the story wasn’t true. After stories about Amina’s situation were featured in the world’s press, it turns out that she was the invention of one Tom MacMaster, a man who says he was raising real issues and meant no harm. (Note: the blog itself has now been closed.) Now many people are furious about being misled. Some in Syria are incandescent with rage that they put their own lives at risk for an idiot with a vivid imagination and a laptop.

Ethan Zuckerman, founder of Global Voices, writes a thoughtful take on the real issues at stake here. Not least, he writes, that MacMaster’s duplicity serves as “a caution to all news outlets that seek to use citizen voices to tell stories in the future. That’s a serious problem.” That’s for sure. MacMaster may not have wreaked the financial havoc of Bernie Madoff, but he’s unwittingly outlined the challenge of verification and identification that faces media companies and journalists looking to use the platform of the Internet to cover global news stories in a timely, useful and accurate manner.

As it stands, news systems using the Internet are at very real risk of being duped by schemers building their very own Ponzi schemes of manipulation and misinformation. And while some organizations, such as the BBC, have extensive policies in place for vetting information coming from social media, it’s clear that the entire platform can get shaky, fast. We imagine the system is built according to our own personal moral code; it’s worth remembering that it’s really not.

The digital age has afforded an astonishing disruption of the news industry. New formats and connectivity have upended what used to be a fairly well understood process of gathering and disseminating news. We’ve all become used to getting instant reports and insights from those on the scene at the time. It’s super exciting to witness the various experiments underway, not to mention painful to witness the inept responses of so many of the incumbent players. Yet as consumers and producers, we’ve become steadily less attuned to judging whether something is fact or fiction, news or opinion. This isn’t merely an abstract issue. On the contrary, it’s too meaningful to allow simply to shake out in the grand scheme of things.

Most often, I write about design. One of my pet peeves is that designers rarely seem able to articulate their value to non-designers. It strikes me now that this is true of journalists too. Journalists (and publishers) have been appallingly bad at explaining why there’s such a process to what they do (or even that there is one.) Instead, they have systematically undermined their own behaviors and fundamental practices in order to try and compete in the new environment. Yet too often, they choose to compete in the most defensive manner imaginable. Too often, online operations of the mainstream press are viewed as the Junior Varsity version of the print-based mother ship, with blogs or Twitter feeds seen less as the front lines of reporting and more as repositories for the breadcrumbs of print stories. Meanwhile, the economics of the new world remain entirely uncertain even as the business model of the old one teeters.

Yet one thing is clear. Both as producers and consumers, we all need to remember to be hypercritical in our thinking and reading and aware that the new sources and resources available are as unsettling as they are exciting. Amina the Straight Man is a timely reminder and a warning of the potential Ponzi scheme that lies directly beneath our fingertips. And these days, we clearly can’t rely on journalists to question everything for us; we must all remember to do the same.

How to Manage Massive Brand Complexity, Target Style

[[Latest word works, this article written for Fast Company.]]

Tim Murray has a daunting job. As creative director of the Creative Vision Group at Target, he oversees the work of 10 agencies, 4 digital partners, and 3 branding studios. And those are the external contributors. Internally, Target, a Fortune 30 company with a market cap of $34.6 billion, has more than 1,200 people working in the marketing department alone. The potential depths of brand and design-related chaos across its 1,755 stores are mind-boggling.

Yet, think of the Target brand, and it’s likely that one image will spring to mind: the Target bull’s-eye, that red ring around a red dot that has come to signify the design savvy and affordable prices of the Minneapolis-headquartered department store.

Last week, Murray took the stage at an AIGA/NY event held at the New School in New York to outline how exactly one goes about producing deceptive simplicity from unfathomable complexity. Alongside him were three of his collaborators, Michael Ian Kaye from Mother, Mary Ellen Muckerman, Wolff Olins’ strategy lead, and Joe Stewart from Huge. Together, the group discussed some successful projects–and even ‘fessed up to a few of the more challenging areas of collaboration.

For instance, this concept caused knowing nods from the audience: the “compliment sandwich.” Essentially, this involves a client giving an elaborate compliment, followed by some pointed criticism, quickly followed up by another compliment. As Muckerman put it, she and her team had come off conference calls feeling buoyant, only to figure out five minutes later that they hadn’t at all been given the go-ahead on a project. “Wait. What? I think they just said ‘no’?”

To his credit, Murray both nodded and laughed. “Target has what we call a feedback-rich culture,” he said gamely. Not to mention it’s a midwestern company to its “prairie roots.” But that, he added, is precisely why Target relies on outside contributors to come up with the biggest possible ideas. That way, as internal politics and processes inevitably chip away at that idea, they might still be left with something useful, beautiful, or unexpected at the end of the process.

Murray also outlined five tips for successfully managing collaboration and complexity:

1. Be Transparent

“You have to be clear that you’re collaborating with others,” he said. “And you have to figure out the roles and responsibilities of the partners and let them know what each is expected to do. Who’ll lead project management? Who’ll decide things? How will things get built?” There’s no one size fits all solution, he added, but making sure that the parameters of each new project are clear and understood from the start is key.

2. Play Nice

“When Target expects you to work with an agency that might be a competitor, throwing elbows won’t earn you the whole business,” said Murray firmly, adding that in fact, agencies that have tried to muscle in on others’ turf have lost credibility, not gained business. “Target won’t spend time disciplining agencies as if they’re unruly children. We won’t hire partners who won’t play nice.” For their parts, the agency creatives agreed this model of work is becoming the norm. “The speed of business demands this type of collaboration,” detailed Muckerman. “The days of an agency being briefed and disappearing for three months to come up with something fabulous doesn’t happen any more.”

3. Be Open

“Trust is the life blood of collaboration,” said Murray. “And good ideas can come from everywhere.” Huge is working on a new version of Target.com due to be launched in the fall. It’s a massive undertaking, as Target moves to design and manage the user experience of the third most trafficked ecommerce site in the world (it’s currently built on Amazon’s platform). “Everyone wants to go to same place so we have to figure out the roadmap to get there, not focus on who’s right or wrong,” said Huge’s Joe Stewart of the working process. “So there might be tons of fighting but we’re fighting together in the same direction.”

4. Stretch the Work

“We often find ourselves connecting the dots between agency partners and shaping a mass of ideas into something cohesive we can support and be enthusiastic about,” said Murray, who also spoke approvingly of the idea that “collaboration is the new competition.” Of course, not all Target ventures are wild successes, but one project with Mother certainly pushed the envelope: The company rented all the rooms on one side of the Standard hotel in New York, staged a fashion show on the High Line, and coordinated a choreographed performance art piece across the hotel rooms themselves. The whole affair was broadcast around the world. “There was an original score, 60 dancers, we had the lighting people from Daft Punk…” said Mother’s Michael Ian Kaye. “It was kind of a big ask.” Big ask = big get. So far, Murray said, the project has earned 180 million media impressions (he didn’t mention related sales figures.)

5. Talk Talk Talk

The final tip of the night was a reminder to keep the lines of communication open at all times. “We had a lot of meetings,” said Wolff Olins’ Muckerman drily of the process it took to develop the packaging and identity for Target’s Up & Up line of some 1200 own-brand products. “The hardest part of the process is to keep people aligned around the strategy.” Murray added: “The only way collaboration works is to be deliberate and consistent over communication. Invite participation; fearlessly put your worst ideas on the table along with the best and pressure test openly.”

As for the bull’s-eye, it turns out even the most successful piece of branding can at times be a millstone. “How many fucking bull’s-eyes do you want?” joked Kaye. “You should see my tattoos,” replied Murray.

NYT paywall: The reality

“I’m all for NYT making gobs ‘o moola off its content. I just don’t think pay wall will accomplish this. I think it’ll do more harm than good,” wrote the journalist and author Adam L Penenberg on Twitter yesterday. At which I breathed a sigh of relief and stopped feeling quite so treacherous about my own doubts and concerns.

Once again, critics have been boxed into taking the “either/or”, “you’re either with or against us” position so beloved by cable TV news. The reality is, of course, rather more nuanced. Of course good journalism is expensive. Much reporting is dangerous and expensive. Of course journalists deserve to be paid for their labor. That doesn’t prevent the NYT proposal from being a superficial solution that doesn’t solve the problem, which is a broken business model that doesn’t work in the digital age. When the powers-that-be finally accept that the basis of their business has dissolved, and that poorly thought-through half-measures don’t come close to forging a new path of sustainable profit, well, then things might actually get interesting. Might. Instead it seems we’re in for another round of tail-chasing.

One of the interesting pieces of fallout from AOL’s acquisition of Huffington Post was the hoohah from bloggers who’d contributed for free and who now wanted a piece of the $315 million pie. Nice try. For many publications, actual writing is an afterthought. When I was an editor at BusinessWeek, all the online columnists on innovation were unpaid—and none of them were journalists. They were consultants or executives who could write off their efforts as a marketing expense. I tried very hard to ensure that their pieces weren’t obscenely self-promotional, but I can vouch for the fact that the editor/writer relationship is a lot trickier when the editor is essentially beholden to the writer’s largesse.

Now the Times is one paper that can point to its original reporting and make the case that it’s attempting not to indulge in such questionable practices. And heaven only knows we need to support smart, on-the-ground reporting and analysis of events such as, this week, Fukushima in Japan or the bombings in Libya. And sure, readers probably should be prepared to pay for this. But as NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen commented on Twitter, “ever worry about that word “should?”.” You can’t make a business on should.

Instead, executives are floundering around with rules for Twitter, rules for links in from Google (now from all search engines) and doing a good impression of people who’ve never been online before. Journalists deserve supportive protectors. Readers deserve quality content. This all seems a little tragic.

For a crazy long but totally hilarious insight into the Times’ decisions over the years, read this wonderful post by former newspaper reporter and Search Engine Land editor-in-chief, Danny Sullivan. As he writes of the leaders of the Times, “Begin weeping for them at any time.” My concern is we’ll be weeping for us all before too long.

Design Thinking Won’t Save You

Recently, Kevin McCullagh of British product strategy consultancy, Plan organized a two-day event for executives to wrap their heads around the concept of design thinking—and, in particular, to think about how they might go about implementing it within their own organization. Kevin invited me along to give an overview of some of the things I’ve been thinking recently. “Don’t hold back,” he advised. So I came up with a talk entitled, “Design Thinking Won’t Save You” which aimed to outline what design thinking is *not* in order to help attendees figure out a practical way forward. Here’s an edited version of what I said:

Ladies and gentlemen, let me break this to you gently. Design Thinking, the topic we’re here to analyze and discuss and get to grips with so you can go back and instantly transform your businesses, is not the answer.

Now before you throw down your coffee cups and storm out in disgust, let me explain that I’m not here to write off design thinking. Really, I’m not. In fact, I’ve been a keen observer of the evolution of the discipline for a number of years now and I’m still curious to watch where it goes and how it continues to evolve as its influence spreads throughout industries and around the world. So to be clearer, I suppose I should say that design thinking won’t save you, but it really might help:

First, some context: Until July of 2010, I was the editor of innovation and design at Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Before that, I’d worked consistently in design journalism both here in New York and in London. The reason that I wanted to join BusinessWeek in the first place was precisely because it struck me as being the one place that had its eye on both camps, on the creative industries and on the business world writ large. And it struck me that it’s at this nexus and intersection that the thriving businesses of the future will be built.

I joined the magazine back in 2006, which was a time when design thinking was really beginning to take hold as a concept. My old boss, Bruce Nussbaum, emerged as its eloquent champion while the likes of Roger Martin from Rotman, IDEO’s Tim Brown, my new boss Larry Keeley and even the odd executive (AG Lafley of Procter and Gamble comes to mind) were widely quoted espousing its virtues.

Still, in the years that have followed, something of a problem emerged. For all the gushing success stories that we and others wrote, most were often focused on one small project executed at the periphery of a multinational organization. When we stopped and looked, it seemed like executives had issues rolling out design thinking more widely throughout the firm. And much of this stemmed from the fact that there was no consensus on a definition of design thinking, let alone agreement as to who’s responsible for it, who actually executes it or how it might be implemented at scale.

And we’d be wise to note that there’s a reason that companies such as Procter & Gamble and General Electric were held up time and again as being the poster children of this new discipline. Smartly, they had defined it according to their own terms, executing initiatives that were appropriate to their own internal cultures. And that often left eager onlookers somewhat baffled as to how to replicate their success.

This is something that I think you need to think very carefully about as you look to implement design thinking within your company. Coming up with ways to implement this philosophy and process throughout your organization, developing the ways to motivate and engage your employees along with the metrics to ensure that you have a sense of the real value of your achievements are all critical issues that need to be considered, carefully, upfront.

Designers often bristle when the term design thinking comes up in conversation. It’s kind of counterintuitive, right? But here’s why: Having been initially overjoyed that the C-suite was finally paying attention to design, designers suddenly became terrified that they were actually being beaten to the punch by business wolves in designer clothing.

Suddenly, designers had a problem on their hands. Don Norman, formerly of Apple, once commented that “design thinking is a term that needs to die.” Designer Peter Merholz of Bay Area firm Adaptive Path wrote scornfully: “Design thinking is trotted out as a salve for businesses who need help with innovation.” He didn’t mean this as a compliment. Instead, his point was that those extolling the virtues of design thinking are at best misguided, at worst likely to inflict dangerous harm on the company at large, over-promising and under-delivering and in the process screwing up the delicate business of design itself.

So let’s be very clear. Design thinking neither negates nor replaces the need for smart designers doing the work that they’ve been doing forever. Packaging still needs to be thoughtfully created. Branding and marketing programs still need to be brilliantly executed. Products still need to be artfully designed to be appropriate for the modern world. When it comes to digital experiences, for instance, design is really the driving force that will determine whether a product lives or dies in the marketplace.

Design thinking is different. It captures many of the qualities that cause designers to choose to make a career in their field, yes. And designers can most certainly play a key part in facilitating and expediting it. But it’s not a replacement for the important, difficult job of design that exists elsewhere in the organization.

The value of multi-disciplinary thinking is one that many have touched upon in recent years. That includes the T-shaped thinkers championed by Bill Moggridge at IDEO, and the I-with-a-serif-shaped thinker introduced by Microsoft Research’s Bill Buxton, right through to the collaboration across departments, functions and disciplines that constitutes genuine cross disciplinary activity. This, I believe, is the way that innovation will emerge in our fiendishly complex times.

Just as design thinking does not replace the need for design specialists, nor does it magically appear out of some black box. Design thinking isn’t fairy dust. It’s a tool to be used appropriately. It might help to illuminate an answer but it is not the answer in and of itself.

Instead, it turns up insights galore, and there is real value and skill to be had from synthesizing the messy, chaotic, confusing and often contradictory intellect of experts gathered from different fields to tackle a particularly thorny problem. That’s all part of design thinking. And designing an organizational structure in which this kind of cross-fertilization of ideas can take place effectively is tremendously challenging, particularly within large organizations where systems and departments have become entrenched over the years.

You need to be prepared to rethink how you think about projects, about who gets involved and when, about no less than how you do things. The way that you approach innovation itself will probably need to change. This might seem like a massive undertaking, but if you’re after genuine disruption more than incremental improvement, these kinds of measures are the only way to get the results that you need.

Design thinking is not a panacea. It is a process, just as Six Sigma is a process. Both have their place in the modern enterprise. The quest for efficiency hasn’t gone away and in fact, in our economically straitened times, it’s sensible to search for ever more rigorous savings anywhere you can. But design thinking can live alongside efficiency measures, as a smart investment in innovation that will help the company remain viable as the future becomes the present.

Somehow, for a time there it seemed like executives thought that if they bought into a program of design thinking then all their problems would be solved. And we should be honest, many designers were quite happy to perpetuate this myth and bask in their new status. Then the economy tanked and as Kevin wrote in a really brilliant article published on Core77, “Many who had talked their way into high-flying positions were left gliding… Greater exposure to senior management’s interrogation had left many… well, exposed. The design thinkers had been drinking too much of their own Kool-Aid.”

The disconnect between the design department, the D-suite, if you will, and the C-suite is still pretty pronounced in most organizations. Designers who are looking to take a more strategic role in the organization, who should really be the figures one would think of to drive these initiatives, need to ensure that they are well versed in the language of business. It’s totally reasonable for their nervous executive counterparts to want to understand an investment in regular terms. Fuzziness is not a friend here. And yet, as I’ll get into in a moment, sometimes there’s no way to overcome that fuzziness. Leaps of faith are necessary. But designers should do everything they can to demonstrate that they have an understanding of what they’re asking, and put in place measurements and metrics that are appropriate and that can show they’re not completely out of touch with the business of the business, even if they can’t fully guarantee that a bet will pay off.

The two worlds of design and business still need to learn to meet half way. Think of an organization in which design plays a central, driving role, and there’s really only one major cliché of an example to use: Apple. But what Apple has in Steve Jobs is what every organization looking to embrace design as a genuine differentiating factor needs: a business expert who is able to act as a whole hearted champion of the value of design. In other words, Jobs has been utterly convinced that consumers will be prepared to pay a premium for Apple’s products, and so he’s given the design department the responsibility to make sure that every part of every one of those products doesn’t disappoint.

He is also notorious for his pickiness. I’ve talked with Apple designers who say he would scrap a project late in the game in order to make sure something is exactly as he thinks it should be. Now I don’t know about you, but how often does a project come back and it’s not quite how you wanted it but it’s ok and it’s really too late to make the changes to make it great and so you go with it? I know I’m guilty of doing that. Jobs doesn’t countenance that approach. And he’s set up processes to ensure that problems are caught, early, and the designers have enough time to get back to the drawing board if necessary. This commitment to excellence has helped turn Apple into the world’s most valuable technology company.

Note too Jobs’ approach to customer research: “It isn’t the consumers’ job to know what they want.” Jobs is comfortable hanging out in the world of the unknown, and this confidence allows him to take risks and make intuitive bets that for the past decade or so have paid off every time. And he’s instilled this spirit in his team. New company leader Tim Cook is renowned for the creative way in which he worked on supplier issues.

So now we get into something of a problem of terminology, because more than likely, Steve Jobs doesn’t consider Apple’s approach to be “design thinking”. Yet he’s the consummate example of one who’s built an organization on its promise. This approach of risk taking, of relying on intuition and experience rather than on the “facts” provided by spreadsheets and data, is anathema to most analysis-influenced C-suite members. But you need this kind of champion if design thinking is to gain traction and pay off.

I once heard a discussion between the current director of the Cooper-Hewitt museum, Bill Moggridge, and Hewlett Packard’s VP of Design, Sam Lucente. Sam was talking about how design thinking had helped him and his team to redevelop the design of one particular product that had done badly in the marketplace in order to produce a later, more successful version. The way he told the story, design thinking meant that this couldn’t be seen as a failure, because every moment had been one of wonder and learning. My interpretation was initially a little less poetic, that in fact design thinking no more guarantees the success in the marketplace of a product than any other tool or technique.

But actually, reframing failure in terms of learning is not just a kooky, quirky thing to do. In and of itself, it’s perhaps a useful exercise. By taking the pressure off design thinking and not expecting it to be the bright and shiny savior of the world, those trying out its techniques will be empowered to use it to its greatest advantage, to help introduce new techniques, to give new perspectives, to outline new ways of thinking or develop new entries to market.

In fact, I would argue, beware the snakeoil salesmen who promise you’ll never take another wrong step again if you buy into design thinking. While some executives have been running their businesses according to its principles for years now, the formal discipline is still pretty new, and individual companies really have to figure out how it can work for them. There’s no plug and play system you can simply install and roll out. Instead, you have to be prepared to be flexible and agile in your own thinking. You’ll likely have to question and rethink internal processes. For there to be a chance of success, you’re going to have to ascertain what metrics you want to use to judge whether a program has been successful or not. And you’re going to have to figure out how to allocate resources to make sure that an initiative even has a chance of taking off.

I know some of you are familiar with the work and thinking of Doblin’s Larry Keeley, with whom I’m working now. For a long time, Larry has been at the forefront of the movement to transform the discipline of innovation from a fuzzy, fluffy activity into a much more rigorous science. His thinking in that arena holds for design thinking too. It’s time to move beyond the either/or discussions so often entertained within organizations. This isn’t about left brain vs right brain. This is about the need for analysis and synthesis. Both are critically important, from data analytics to complexity management to iteration and rapid prototyping. But even with all of this, there’s never going to be a way to 100% guarantee success. The goal here is to be able to act with eyes wide open, to have a clear intent in mind and to have systems in place that allow you to reward success and quickly move on from disappointment—and to make sure that your organization learns from those mistakes and thus does not repeat them.

A Happy Story of Stellar Service

I recently helped to organize a trip to Miami, to celebrate a dear friend who’s getting married in May. The long weekend went well, a good time was had by all, etc etc. Yet I was particularly thrilled and gratified by the experience we had at Michelle Bernstein’s restaurant, Michy’s.

For some time now, service has been talked of as an important factor to consider within innovation. It’s one of Doblin’s “ten types” of innovation, and “service design” has emerged as an important discipline in its own right. Practitioners such as Hillary Cottam in the U.K. demonstrate what’s possible when you apply smart design principles to systemic matters of great weight, such as the justice system or healthcare.

This was rather more straightforward: a restaurant doing things right. Here’s what stood out for me during this lovely evening:

The menus

I’d had fairly involved discussions with someone at the restaurant before our group even showed up, and during one of these conversations I mentioned that we were celebrating my friend. “How lovely. Would you like us to customize the menus?” was the instant response. I hadn’t even thought of this, but it was a lovely touch that lent a carefully designed feel to the evening.

The food

Chef Anthony Bourdain once described vegetarians as “persistent irritants,” and declared that he’s delighted to charge a fortune to serve them a couple of pieces of grilled eggplant. Don’t think they, er, we don’t notice. We may not eat fish or meat, but we’re not stupid. Here, in contrast, there was neither huffing nor puffing about the one vegetarian in the group demanding special treatment. My friends actually wanted to try my food too. I can’t tell you what a rare occurrence that is.

The thoughtfulness

Giving a bride-to-be an unsolicited dessert with the word “congratulations” written on the plate makes her very happy. It also makes the organizers very happy that they went to that venue.

The service

None of us were driving so we relied on taxis to transport us back to our hotel after the meal. As we loitered outside the restaurant waiting for a car to arrive, the hostess came to check on us. “I’ll come and get you if one doesn’t arrive in five minutes,” I said to her. “No. I’ll come back and check on you in five minutes,” she replied. She did, too.

It strikes me as a bit sad that good service should still be a moment of wonder rather than an expected part of any experience. But as I’d bet everyone could attest, that’s not the way of the world. So hell, I’ll take it.

The real theater on display at Christian Marclay’s exhibition

If you didn’t hear about it, the artist Christian Marclay’s The Clock was on show in New York recently. Essentially, it’s a 24 hour abstract film: Marclay expertly spliced together thousands of excerpts from movies old and new, familiar and foreign. Each shot is somehow related to time–and the whole thing plays in real time. So if you popped in at 4.30 pm, you’d more than likely watch clips about afternoon tea. Visit one of the late night showings and see rather racier clips. (That’s pure hearsay: I turned up at 10 o’clock one Friday night and the line stretched a two hour wait around the block and I wimped out and went home.)

The show has received raves pretty much everywhere it’s played. See reviews here, here and from the London show, here. And for what it’s worth, I agree with the experts. The film is totally mesmerizing. I watched, spellbound, for three hours, and only reluctantly dragged myself back to life’s more regular programming.

What was even more mesmerizing, however, was the behavior of the assembled masses. As I waited to get in, one of the security guards regaled me with some excellent stories of the tantrums people had tried to pull in order to jump the line. (Just an aside, but if you ever hear yourself uttering the immortal phrase, “Don’t you know who I am?” it’s time to have a serious word with yourself.) This guy wasn’t fazed in the slightest. “I don’t care if you know Miz Cooper, Mr Marclay or the Pope,” he said vehemently. “I’m not ruining your life. I’m doing my job.” And do it, he did.

There was some even more amazing theater on display once you actually got inside. You can see the layout of the space below. What’s not so clear is that there weren’t enough seats to go round. At least half the crowd had to stand or sit alongside the edges of the gallery. Initially, for instance, I got a spot sitting halfway along the right hand wall—and I quickly realized that the subplot of the film was going on in the room itself.

Whenever someone got up from a sofa, it sparked a quiet, fierce, intense and entirely mean-spirited free-for-all. I saw two women lose all sense of decorum as they pelted towards one spot, one of them throwing her bag onto the seat, the other throwing up her hands in silent disgust. I even got caught up in it myself. I moved to take a seat that opened up right next to where I was—but moved way too slowly. Suddenly, some guy came out of nowhere, skidded past me and plonked himself down. I stammered unintelligibly—I’m excellent in a crisis—and then he played a devilish joker card. “Do you mind?” he said as he settled in. “I don’t feel at all well.” (Later on, of course, I came up with all sorts of witty comebacks as to why he should clearly go home and I should get to sit down. At the time, I meekly slunk back to the wall again, throwing up my own hands in silent disgust.)

I’m not sure it’s quite what Marclay had in mind when he put together his masterpiece, but the additional elements of musical chairs and Benny Hill actually enhanced the experience. Not to mention provided a useful reminder: never hesitate.

Images © Christian Marclay. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Ryan Jacoby: The Seven Deadly Sins of Innovation

Ryan Jacoby heads up IDEO’s New York practice, and gave a talk at NYU/Poly this evening with an intriguing title: Leading Innovation: Process Is No Substitute. It points to the tension found in companies between right-brainers (for lack of a better term) espousing design, design thinking and user-centered approaches to innovation and the left-brained, more spreadsheet-minded among us. Now, bear in mind that most C-suites are dominated by the latter, all of whom are big fans of nice neat processes and who pay good money to get them implemented rigorously throughout their organizations. Jacoby’s point: processes are all well and good, but they don’t guarantee innovation, and in some cases they might even provide a false sense of security.

Ryan outlined what he described as the Seven Deadly Sins of innovation, which I’m sure will ring true for most people who’ve worked on such projects. They are:

1: Thinking the answer is in here, rather than out there

“We all get chained to our desks and caught up in email,” he said. “But the last time I looked, no innovation answers were coming over my Blackberry.” You have to get outside of the office, outside of the conference room and be open to innovation answers from unexpected places. Ryan makes himself take a photograph every day on the way to work, as a challenge to remember to look around him. (My homage to this idea above, a random image from last weekend’s jaunt to an icy upstate NY.)

2: Talking about it rather than building it

This one related to the last. At least here in the U.S., we live in a land of meetings and memos and lots and lots of discussion. Sometimes it’s more than possible that all this talk might prevent us from, well, actually doing anything. He gave a great example of an idea to bring “fun into finance”, and showed a mocked up scenario of a guy buying a pair of sneakers, at which point a virtual avatar danced on his credit card. Practical? Not the point. The unpolished prototype motivated the team and got them thinking differently.

3: Executing when we should be exploring

“This is huge for management types,” he said, going on to warn of the problem of trying to nail down a project way too early in the timeframe. “Who’s exploring? Who’s executing? Where is everyone in process?”

4: Being smart

“If you’re scared to be wrong, you won’t be able to lead innovation or lead the innovation process,” he said. This is huge. Innovation is all about discussing new ideas that currently have no place in the real world. If you’re only comfortable talking about things that *don’t* strike you as alien, chances are you’re not talking about real innovation.

5: Being impatient for the wrong things

Innovation takes time, but too often executives expect unrealistic results at an unrealistic clip. Be explicit about the impact that you expect.

6: Confusing cross-functionality with diverse perspectives

IDEO is an inter-disciplinary firm, mixing up employees with a whole host of backgrounds. That’s different from teams that simply mix up functions–and critical to ensuring a better chance at innovation. “Diversity is key for innovation,” said Mr J.

7: Believing process will save you

Here, Ryan showed a great image of vendors touting their wares at the Front End of Innovation conference in Boston. His point: you can’t simply buy your way to a soaring innovation strategy. Some of these products might be useful, sure, but they’re no substitute for real thought leadership. Or, as he put it, “learn the process, execute the process, and then lead within it.”

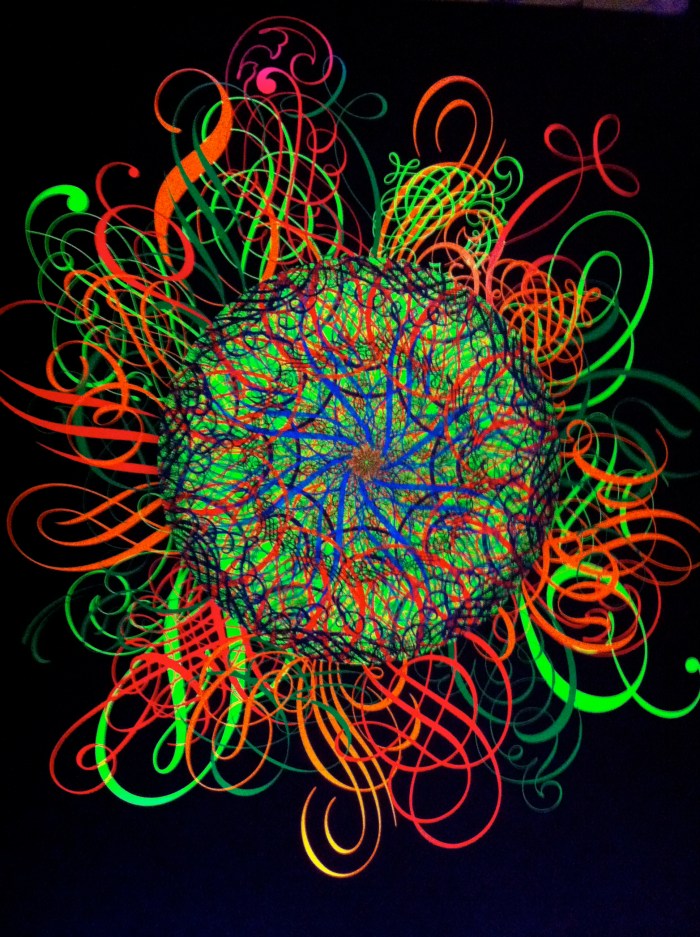

Ryan McGinness: Black Holes

Last night, I went to celebrate artist Ryan McGinness’ latest installation, at Philips de Pury in Manhattan. Black Holes is an exhibition of work McGinness created from 2004-2010. The large round canvases are deceptive. On first glance they look like fairly simple spirograph-style images. But stand in front of them for any length of time, and get drawn in inexorably by the delicate, hypnotic shapes. Black holes, indeed.

For this exhibition, McGinness added a neon flourish, adding delicate wisps of vinyl around some of the canvases and lighting them with fluorescent light. One long stretch of these can be seen from the High Line walkway, sure to confuse and delight late-night tourists. Somehow the effect transcends the usual gaudiness of neon and is bewitching, poignant, and glorious. As are the newest, black-on-black canvases, which are subtle but somehow defiantly perfect. Gorgeous.